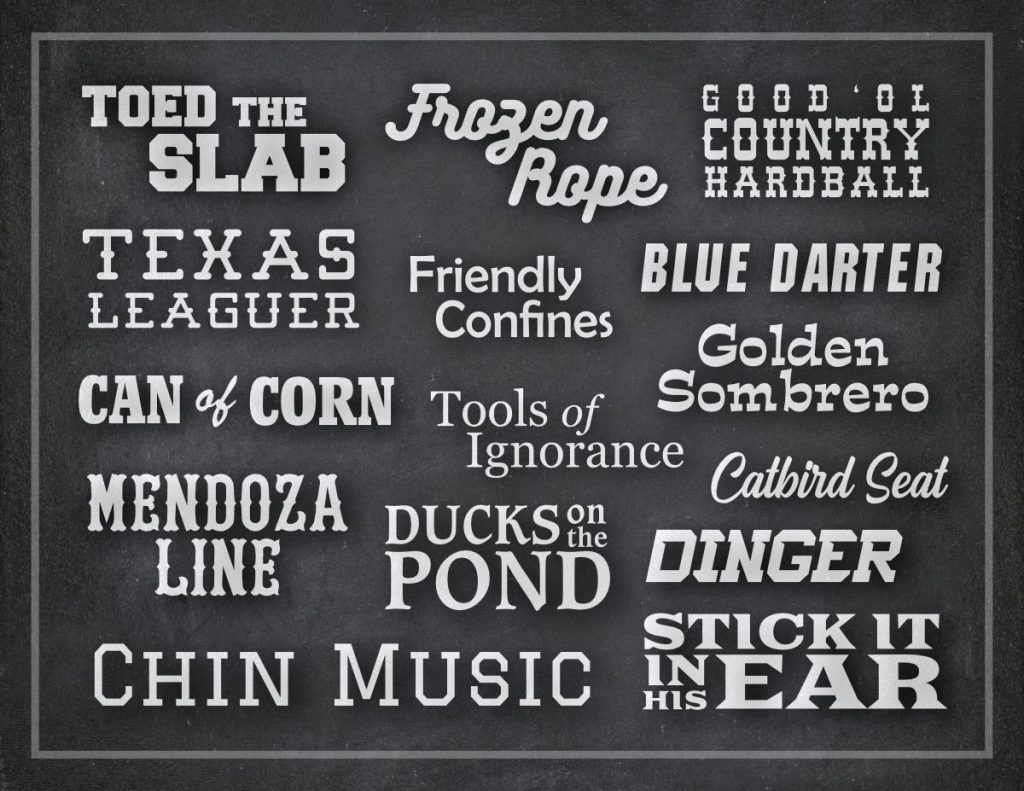

Baseball cliches: The writing is on the wall

BY GLENN MILLER

Roy Hobbs Baseball

Our backs were against the wall. It was do or die. We were playing for all the marbles. There was no tomorrow.

Actually, we had plenty of tomorrows at the time.

It was late June when Roy Hobbs Baseball president Tom Giffen and I discussed stories and blog post topics for this edition of the Inside Pitch.

At the time – no surprise! – I had the MLB Network on my TV. I mentioned that Houston Astros ace Justin Verlander had toed the slab.

Toed the slab?

Good grief!

That was it.

Tom suggested I write a blog post about baseball cliches. He did not use the term “old” baseball cliches. As a former newspaper sports editor Tom knows the adjective old in front of cliche is superfluous.

Cliches by their very nature are old. If one of his writers in Tom’s days at the Akron Beacon Journal had turned in a story with as many cliches as fill this post, Tom might have bellowed, “Take thee and thou typewriter to a nunnery!”

Or words to that effect.

Do not pass Go.

Do not collect $200 in severance pay.

As all Roy Hobbs players know, the game’s long history and unique nature has allowed it to develop a rich history of cliches, or hackneyed phrases.

Oh, a big help in compiling these cliches were numerous websites but most helpful was “The Dickson Baseball Dictionary,” which was published in 1989.

As legendary Bronx Bomber skipper Casey Stengel used to say, “You could look it up.”

We did.

So, here we go with the cliches:

Heralded right-hander Justin Verlander toed the slab recently when the Houston Nine visited Gotham for a match against the Metropolitans.

They weren’t in the Friendly Confines in the Windy City.

His opponent that day wasn’t a crafty lefty of lore such as twirler Jamie Moyer.

Any pitcher, whether a fireballer or a savvy mound tactician, hopes batters hit just weak cans of corn to the outer garden.

A frustrated pitcher may at times with hard cheese throw chin music.

We don’t recommend any form of bean ball meant to stick in somebody’s ear. We don’t even want brushback or knockdown pitches and certainly don’t buzz the tower.

Such unsportsmanlike conduct can lead to bench-clearing donnybrooks and somebody may start throwing haymakers. A haymaker should not be confused with Morris Buttermaker, the Walter Matthau coach in “Bad News Bears.”

A pitcher with a good curveball throws Uncle Charlie. One-time Metropolitans ace Dwight Gooden’s curveball was so outstanding it was referred to as Lord Charles.

In his prime Gooden likely allowed few blue darters or screaming meanies or frozen ropes.

A weak Texas Leaguer falling onto the greensward is vexing to pitchers. Even if the outfielders get on their horses, they can’t catch all those Texas League bloops. A dying quail often results in the batter reaching the initial sack and then then keystone sack and eventually home plate.

Especially if the bases are drunk, somebody will get a Ribbie when he socks the ball and a player plates a run for his team.

Sometimes outfielders make circus catches to prevent teams from circling the bases.

If a pitcher attempts to throw breaking pitches but they don’t break they are said to be “cement mixers.” The pitcher is then toast and a call to the bullpen for a fireman is likely.

If many runs are plated the skipper may go to the bump and say to his backstop wearing the tools of ignorance about the pitcher, “Stick a fork in him – he’s done.”

Meanwhile up in the broadcast booth, a former player may be saying of a swift player, a speed merchant, “He has good speed.”

Good speed?

What is bad speed?

Multiple base runners means, of course, ducks are on the pond. That presumably has nothing to do with slugger Ducky Medwick, a Hall of Fame slugger who played for the Gas House Gang. His teammates included Pepper Martin and Dizzy Dean.

Ducks on the pond? According to “The Dickson Baseball Dictionary,” the first recorded use of the term was in the San Francisco News on Aug. 5, 1939.

Pitchers sure don’t like hitters bashing a big fly or dinger or going yard or dialing long distance or hitting a tater or a round-tripper or circuit clout in a game of good, old country hardball. Hall of Fame pitcher Dennis Eckersley, who is credited with coining the term “walk-off homer,” says of hitters bashing circuit clouts that they went bridge.

The ultimate indignity for hurlers and twirlers and mound men is likely the walk-off homer, no doubt the bane of their existence. That should never be confused with Eddie Bane, who pitched for the Twins for three seasons in the 1970s.

Batters scuffling along below the Mendoza Line (.200) rarely hit a big fly. Other than Hall of Famer Bucketfoot Al Simmons, it’s tough hitting with one’s foot in the bucket. By the way, Simmons played spring training games with the Philadelphia A’s at Terry Park in the 1920s and 1930s.

Hitting below .200 is also said to be on the Interstate.

Players struggling so mightily might strike out four times in a game and earn the dreaded Golden Sombrero.

They may feel as if every day an outfielder makes a circus catch to rob them of a bingle, another term for a base knock.

A player with a batting average that low is never a five-tool player.

Teams with a chance of reaching October baseball and the Fall Classic may look at the all-important loss column to see how their chances against the front-runner are shaping up.

First-place teams often occupy the Catbird Seat.

We haven’t mentioned all the baseball cliches. More are out there being uttered by players, coaches, fans and broadcasters.

There are too many to mention here.

But we will close with a cliche that wasn’t around when “The Dickson Baseball Dictionary” was published in 1989.

In 1992, the beloved baseball film “A League of Their Own” was released.

It contained words from actor Tom Hanks playing Jimmy Dugan in which he famously said, “There’s no crying in baseball.”

It is now a cliche.

Just one more.